The nitpicker Max White is our opponent. White is a solid player, meticulous but adheres to ancient principles long debunked. A kind of visionary error that overlooks routine things. Max White, by trade, is a scientist. Born and soon indoctrinated to research something important but never get it published. Knows something, but seems unable to play it over the board. Mistakes always conceptual. That’s one version anyway.

This game starts with convention, with solidity, with antiquity, an eternal game where owning a goat still means something. White, 35s. Roll the home point, make the home point. Next day, Black does the same with Black 42s. The questions clarify as simplicity seeps into each corner of the board.

White buys some supplies with White 23s by engaging those spares from the midpoint. White brings both builders into the outfield. A slap of the hat to a 1970s backgammon mystique. White hopes next to make the golden or the silver home point.

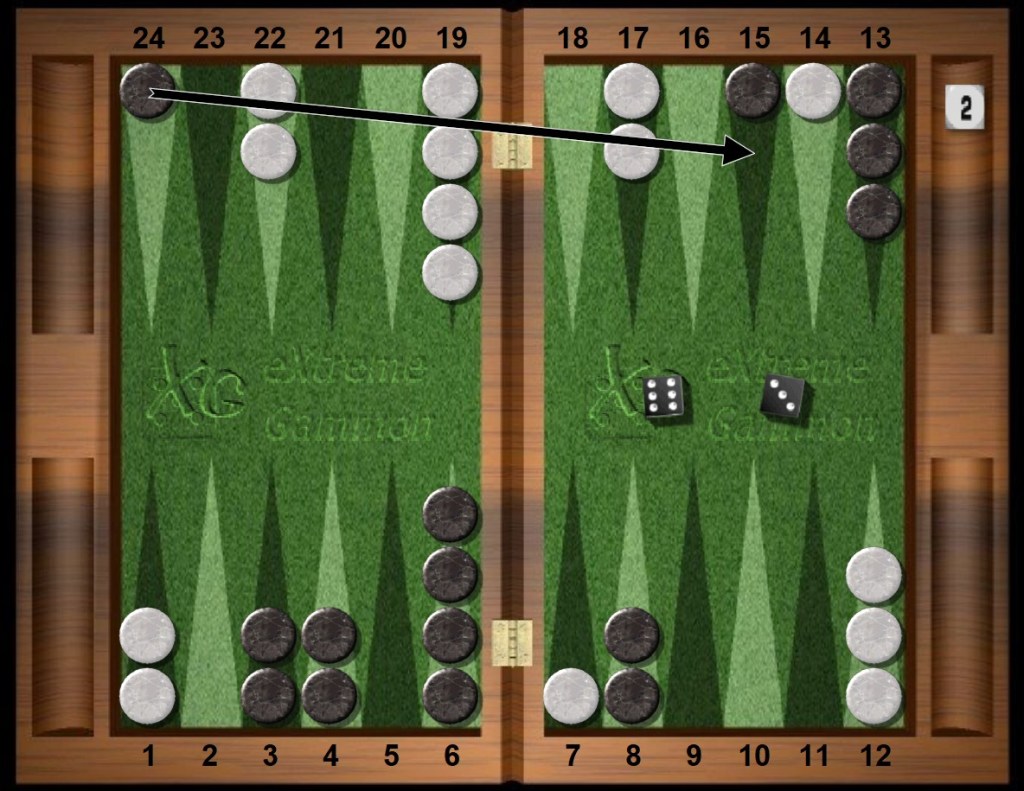

Black draws first blood with a nine by a hit and run of a white blot.

White dances on a two-point board.

Hit-dance-double. Hit-dance-cube. A calypso rhythm that a good backgammon player feels from time to time.

To recap: Both players open strong, White creates two spare blots, Black hits one, White dances with no paparazzo in sight and then, in the blink of an eye, Black contemplates a first cube.

“How much is this game for?”, Black taunts.

Max White blinks.

Black doubles.

White takes.

White takes a picture of the cube position with his phone, a routine reflex these days to any early double. White snaps another pic after Black rolls a market loser, the noble 55s, but already White has taken the bait. Just more photographic evidence of Lady Luck’s caprice, or so Max White says.

Early doubles must be based on optimism. Be a joyful giver and a joyful taker as a youth. How’s that for late advice?

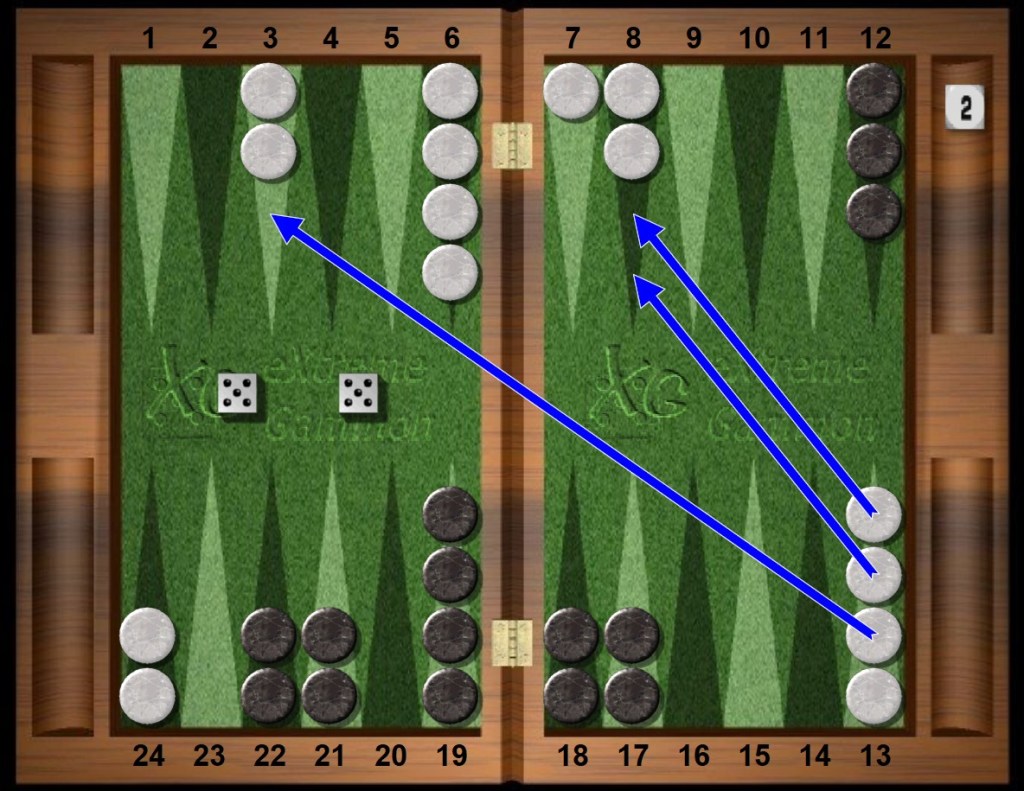

White starts Black’s barpoint with the dancing white checker.

Black refuses to hit the white blot with the six but instead pairs his runners in the outfield. The unanswered hit of the white blot has put Black ahead in the race by five rolls. Black also boasts the better home board. Structures are still intact. Situation cubed. Game needs to be put to bed for the night.

White wants a six, White needs a six, but at least White 45s can tidy up both blots, and save plenty of gammons. Drawback, that pesky ace point anchor.

Black rolls 44s. Nearly clinches the deal. Black wins most games with a four-to-one tally. What can possibly go wrong?

White rolls double 55s, but the runners are still in lockdown. A flashback to the 1970s takes hold in Max White’s febrile mind, some drivel about timing advantage, and inexplicably White volunteers a free blot by breaking the midpoint. Providing an egregious affront to the vital need for connectivity.

Black misses the hit. Black spreads out spares.

With 16s, White again leaves the free blot! The concept of timing run amok.

Black misses the hit again with 43s. Midpoint transforms into outfield blots vulnerable to some white fours.

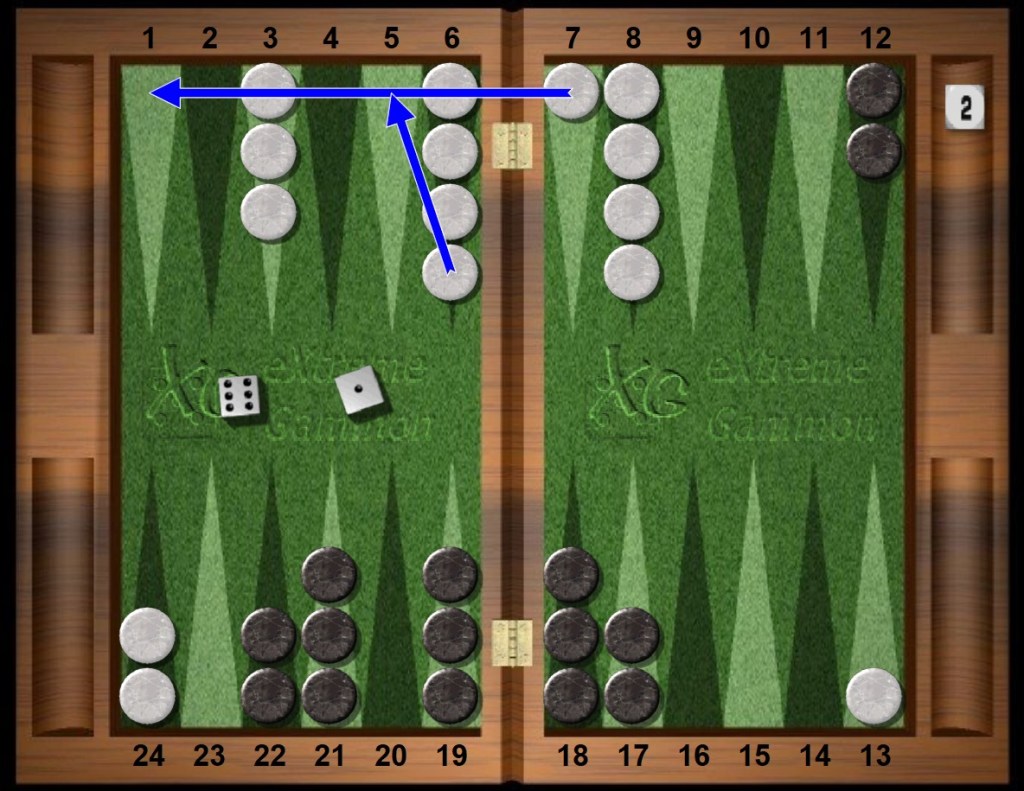

Praise be. A miracle of middle east proportions. The white play does everything.

Black’s gut follows the script of this horror flick … wait for it … that’s right … Black dances. Then White redoubles to 4. Black breathes deeply, and takes the recube.

White rolls to disengage.

A new dawn. A solitary black blot enters and stops, confronting a wall of white checkers.

White attacks with care. Black spends a stint on the bar.

Black enters. Perfect scene for a last ditch fight in the outback. Will it happen?

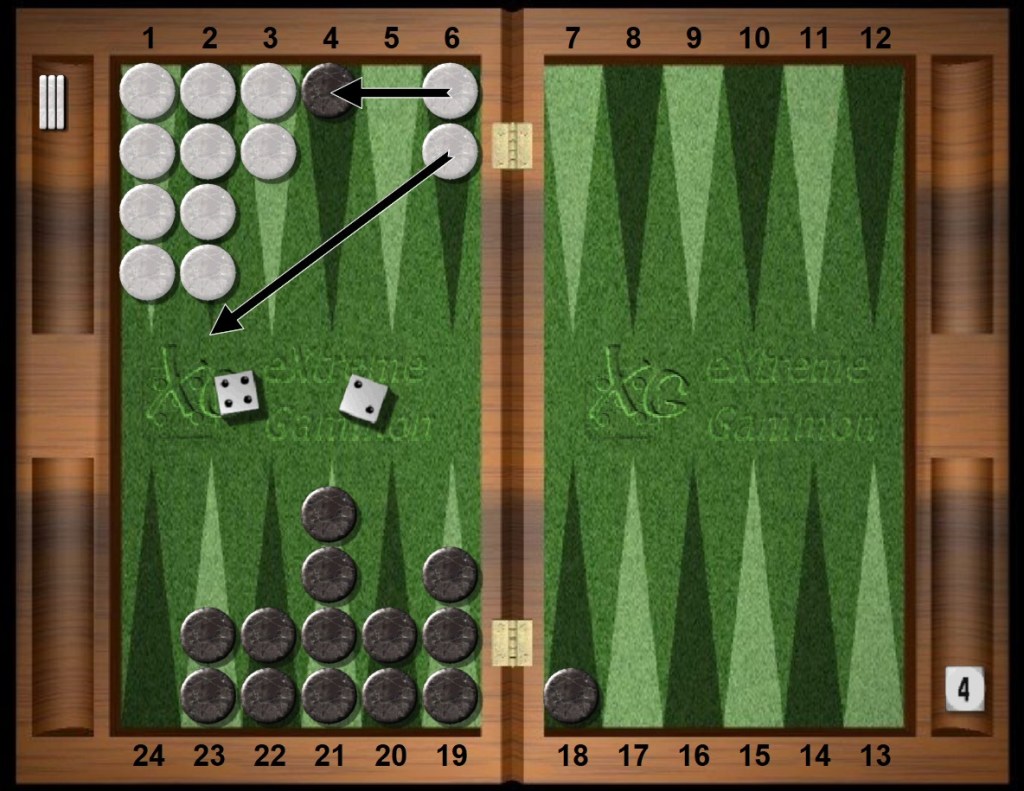

Counting shots here uses the pattern of hi-low split, meaning higher 6xs-5xs-4xs dice will blot, but only when the other die is low as 1xs or 2xs. The hi-low count totals a dozen shots, (3*2*2), precisely one-third.

Does the hit happen in the game? White leaves a blot, yet hits the black blot loose onto the bar, thereby upping the gammon chances.

Black dances, obviously missing. Now what is the shot count for another try? Any two white dice bigger than deuces again leave a vulnerable blot. Perhaps this shot count is a snippet of Pascal’s triangle, or perhaps not — three 4s plus two 5s plus one 6s, twice each, thus yielding another dozen shots.

And there it is … another white blot. A direct eleven black shots. Only Black rolls 41s from the bar.

Black misses but saves the gammon. Only a four-point loss. Only?

In backgammon, each game plays two stories: the one involving emotions, and the other story — the austere story on the familiar board. That story counts, and captures your obsession. With the jolt of a dice roll, it ushers you into a backward morass, and bids your mind adieu.

An adventure tale like Gulliver, but without the travel.